There are lots of things that investors believe which I find perplexing. The Superbowl indicator is one, but the oddest to me is the so-called Fed Model, also known as the IBES Valuation Model.

It is not that the Fed model is so terribly wrong — it has been both right and wrong over the years. Rather, it is the way too many people conceptualize it.

First, the definition of the Fed Model: Yield on the 10-year U.S. Treasury Bonds should be similar to the S&P 500 earnings yield (forward earnings divided by the S&P price). This, in theory, should inform you of when equities are over-priced or under-priced.

Note that the formula contains two variables: While it is commonly described as a way to evaluate when stocks are over- or under-valued, the other variable in the formula above is the forward S&P500 earnings consensus. SPX prices and the 10 year yield are the knowns, while BOTH valuation and forward earnings estimates are the unknowns.

Thus, the Fed model today might be telling you either of two things: When equities are undervalued — or when consensus earning estimates are simply too high.

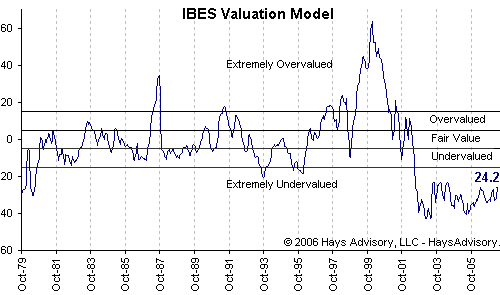

Let’s see how that looks on a chart:

>

graphic courtesy of Hays Advisory (June 2007)

>

Looking at the chart above, we can identify some rather odd periods. The model had stocks extremely undervalued in 1979 — just before a major 30% selloff. In 1981, stocks were fairly valued on the eve of the greatest bull market in history. From 1982-85, stocks bounced between slightly overvalued to undervalued, according to the model. In 1987, a very timely crash warning. 1998, an extremely early crash warning, missing a huge 2 year run in the indices. In 2001, it had stocks as undervalued — and they proceeded to get a whole lot cheaper over the next 2 years. Equities have been extremely undervalued ever since.

Now, given that rather inconsistent track record, I find it hard to get too excited about this. But the most damning evidence against the Fed model is the period prior to 1960s. Over that entire, the Fed model had no utility whatsoever. “Out of sample” testing — looking at a different set of data than the one proffered — is quite damning to the Fed model.

Now, given that rather inconsistent track record, I find it hard to get too excited about this. But the most damning evidence against the Fed model is the period prior to 1960s. Over that entire, the Fed model had no utility whatsoever. “Out of sample” testing — looking at a different set of data than the one proffered — is quite damning to the Fed model.

Which brings us back to today. We continue to see the Fed model used to rationalize a bullish stance in equities. However, given that it is based in large part on analysts consensus for future SPX earnings, investors need to be extremely cautious relying solely on the Fed model. Why? Analysts are unflaggingly inaccurate at turning points. Example: Q3 S&P500 earnings consensus were +8% — S&P500 earnings came in at -8%. Q4 has been similarly lowered, undercutting the earlier forecasts of undervaluation.

Now let’s look at 2008. S&P 500 forward earnings over the next 4 quarters are as follows: Q1 = 3%; Q2 = 4%; Q3 = 20%; Q4 = 50%, according to UBS.

So stocks, so we are confronted with two possibilities. Perhaps, equities are seriously undervalued (that assumes earnings explode in 2H). An alternative explanation, and one I suspect is more likely: Analysts consensus earnings are wildly exuberant for the second half.

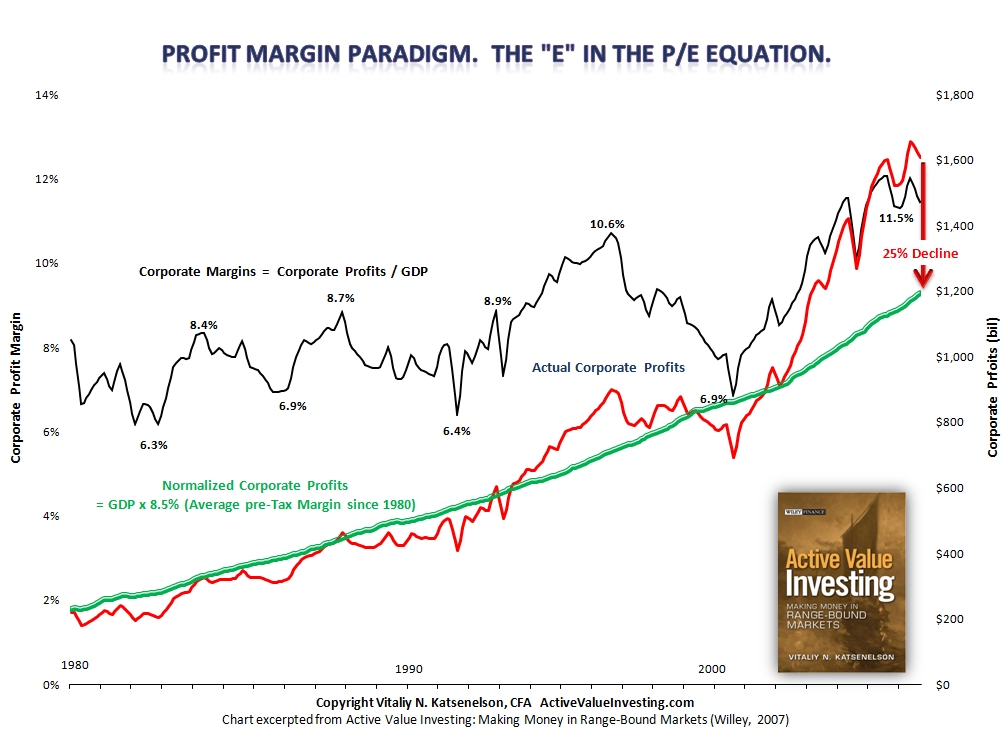

One last issue: Let’s ignore the analysts, and merely consider mean reversion: As the chart below shows, earnings have been unusually high relative to history. If they merely mean revert, they will come down another 25%. Even worse, most mean reversion blows right past historical averages to opposite extremes.

>

Graphic courtesy of Vitaliy’s Contrarian Edge, from the book Active Value Investing: Making Money in Range-Bound Markets

>

The bottom line — either equities are extremely under-valued, or analyst consensus earnings are significantly too high.

But to treat the Fed model as if it merely looks at valuation is to ignore a key variable — future earnings consensus — that tends to be wrong at the worst possible moment . . .

>

Sources:

Active Value Investing: Making Money in Range-Bound Markets

by Vitaliy N. Katsenelson

Wiley, September 28, 2007

A Profit Fumble — or Not?

TOM LAURICELLA

WSJ, February 4, 2008; Page C1

http://online.wsj.com/article/SB120208551253339345.html

Fight the Fed Model: The Relationship Between Stock Market Yields, Bond Market Yields, and Future Returns

CLIFFORD S. ASNESS

AQR Capital Management, December 2002

http://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=381480

The Fed Model: The Bad, the Worse, and the Ugly

JAVIER ESTRADA

IESE Business School January 2006

http://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=877245

Solving the Price-Earnings Puzzle

CARL CHIARELLA

University of Technology, Sydney – School of Finance and Economics

SHENHUAI GAO University of Sydney – Economics and Business

April 2002UTS Working Paper No. 116

http://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=880002

Blog Synthesis: Gunning for the Fed Model?

http://www.cxoadvisory.com/blog/internal/blog-fed-model/

The model should be discounting earnings to inflation, not bond yields:

http://www.cxoadvisory.com/REY-details/

Taking into account the fact that inflation is understated, the valuation perspective changes dramatically…

First, the definition of the Fed Model: Yield on the 10-year U.S. Treasury Bonds should be similar to the S&P 500 earnings yield (forward earnings divided by the S&P price).

Sorry but this has the bullshit meter tipping off the scales. Since when has it been assumed that the return on risky assets should be roughly the same as the return on government bonds. If people actually believe that statement then there is little wonder the financial markets are in a mess.

Stocks carry significant risk (think enron)and should produce significantly higher returns over time – recalibrate that chart to stocks earning bonds plus 3-5% and see how it looks. I would guess even more idiotic than you are rightly suggesting.

BR – Couldn’t this model be skewed by bond yields being “artificially” low? It seems as though the conundrum of lower 10-yr yields could be as much a driver as equity valuations.

Thanks!

There has been way too much ink and too many bytes wasted on this POS idea. Asness’ piece is very good if you haven’t read it.

I can debunk it very quickly–if the 10 year Treasury trades to 1%, do you really think the market PE should be 100? Just ask the Japanese how that is working out for them.

Put the “Fed Model” in with Ben Stein!

This model is flawed in so many ways as to be completley irrelevant. Aside from the facts already stated, the yield curve has been distorted by the same Bretton Woods II perversions that have resulted in the other excesses and bloodletting in the economy. perhaps it is a bit to coincidental that Bush is out stompoing for free tradem, when the serious moves in academic circles is to reassess the value of “free” trade. The treasury curve as the short view in the FT points out today is massivily overvalued – asset bubble (just harder for people to realize that the governement is yt again expropriating their savings with supressed yields. The system is now so corrupt and perverted the government has got to be thanking their ucky stars for the “forced” 401K flows into equity markets.

I can debunk it very quickly–if the 10 year Treasury trades to 1%, do you really think the market PE should be 100? Just ask the Japanese how that is working out for them

It could go higher than that… certainly if eps go to near 0!

John Hussman has written extensively about the problems with this model. One of his points is that the 10-year Treasury is not the proper comparison, because the effective duration on a common stock is much longer than the duration on the Treasury.

I think Mike makes an obvious point. The current rate on the 10 year bond has nothing at all to do with expectations of return. I bought a 10 year TIP last spring that has a yield of 2.6% + the CPI.

Is there really anyone who thinks inflation is going to be less than 1% for the next 10 years? If it is, it will be because we are in a severe deflationary episode and the stock market will be in for a hell of a lot more pain.

Analyst earnings estimates are way too high. Does anyone really think 4Q08 earnings are going to show 50% growth? In the last 20 years (all I have data for) S&P500 earnings growth has never been better than 35% quarter over quarter.

As someone mentioned before, John Hussman has pointed out the flaws in the Fed model many a time. Look at trailing earnings rather than forecast earnings, particularly at turning points such as we are experiencing now.

hmmmmm let’s see the Fed endorses a model that shows stocks are cheap relative to what????

if the Fed was not actively engaged in removing most options for investing and forcing people to buy equities, based on it’s actions that have affected bonds and currency I might be inclined to give it some merit.

But since it makes absolutely no sense and relies on P/E ratios that are not really indicative of what the valuation is really worth…I’ll pass.

Case in point….AMZN is a “value stock” with a p/E ratio well north of anything resembling value.

Ciao

MS

Barry, not only are you right, but you get serious kudos for straightforward and cogent explication. right on ya mate!

Time for another round of rate cuts?! Come tomorrow it will be 5 days and we haven’t had a rate cut.

But stocks are cheap, compared to your house!

Bernanke must get rates to 1% again FAST, so that he and Greenie will forever be linked as the two worst central bankers… of all time. (i wonder how the Fed model looks if you use trailing 10-yr actual earnings and yields instead of forecasts. certainly no one knows what’s happening years or quarters out when they often cant explain what’s happened to their businesses in the Q just ended)

Seems everyone agrees the model is seriously flawed – case in point Japan.(ZIRP)

The US is now close to ZIRP, or will it be

ZIRPOLA

(zero interest rate policy or less America).

If a “new and improved” method were used

in the new world economy, wouldn’t you use

the S&P’s PE ratio and use the yield on

Australian bonds or Euro Bonds (or both) to see how cheap or expensive the S&P really is,

or better yet, tie in

maybe some other world index(s) compared to bond yields of the world.

Now doesn’t that sound like fun????

Steve Bowles:

The idiotic defense I’ve read for why people can conceptually accept no equity risk premium in the FED model formula is that it gives you a “free” option on growth. So when you consider the value of that implied option, it does take into account an equity risk premium.

The entire framework is retarded and provides stupid results at the extreme as everyone recognizes with the Japanese experience.

The UBS numbers appear to reflect operating earnings rather than as-reported earnings.

S&P’s numbers for operating earnings are:

Q3 at $25.13 versus $20.87, up 20.4%, and

Q4 at $26.66 versus $17.12, up 55.7%.

For the full year, $97.99 versus $84.44, up 16%.

S&P’s as-reported numbers are very different:

Q3 at $17.10 versus $15.15, up 11.4%, and

Q4 at $14.30 versus $14.50, down 1.4%.

For the full year, $67.90 versus $72.86, down 6.8%.

Disparities between operating and as-reported earnings numbers were a defining characteristic of the late-bubble and bursting-bubble years, when it was difficult to even have a rational conversation about valuations.

Barry,

The beauty is that as investors we don’t have to buy the whole “market”, we have the opportunity to buy individual companies. In 2000 & 2001 if you looked at the “market” in general, the valuations looked very expensive relative to any metric you wanted to throw at it. However, if you looked away from tech, and the Vanguard 500 Index bubble stocks (Bogle got a free pass on that one) there were great bargains to be had, selling at low fundamental valuations, and investors that looked away from the crowd did pretty well.

As investors we have the choice not to buy imploding or overvalued situations, we don’t have to buy the “market”.

As Jeff Matthews states on his Dairy Queen/Berkshire analysis “Thus a more objective way to look at the sales price of Dairy Queen would be to simply compare it to the cost of money, which is how most rational buyers—Warren Buffett especially—determine valuation.”

The cost of capital for well heeled buyers has been greatly reduced, and many equites have been crushed. That is an interesting combination for specific company situations.

Street Sleuth: Fed Model May Distort Stock View; Valuation Tool’s Outlook For S&P 500 Overstates Bull’s Case, Critics Say

March 22, 2004

According to the minutes of its January meeting, some members of the Federal Reserve’s policy-making committee worried that financial-market valuations “left little room for downside risks.” But the central bankers couldn’t have been talking about stocks — at least not if you buy into the idea that they were using the valuation tool that is often referred to as the “Fed model.”

To the contrary, using the Fed model, which looks at the relationship between stocks’ price-to-earnings ratios and the yield on the 10-year Treasury note, stocks are wildly undervalued. Right now the model says the Standard & Poor’s 500-stock index should be more than 50% higher than it is.

But don’t reach for the party hat just yet. Even the people who use this sort of valuation metric think that it overstates the bull case.

In its simplest form, the Fed model holds that the 10-year Treasury yield and the earnings yield on the S&P 500 (expected earnings over the next year divided by price — the inverse of the price-to-earnings ratio) should be the same. When Treasurys yield more than stocks are expected to, for instance (as they did through the late 1990s into 2002), they are a more attractive investment than stocks. When they yield less than stocks, it is time to shift money back into the stock market.

The notion that the Federal Reserve watches this relationship was first put forth by Prudential Equity Group chief investment strategist Edward Yardeni and derives from the Fed’s July 1997 Monetary Policy Report to Congress, which said that the 10-year Treasury yield exceeded the S&P’s earnings yield by the largest amount since 1991.

In fact, similar valuation methods had been used for years before the Fed mention, and many institutional investors continue to employ them.

“The Fed model is prevalent from my experience,” said Carlos Asilis, a portfolio manager at the hedge fund Vega Asset Management. “Major asset allocators like insurers and pension managers look at it closely.”

A problem with the model now, Mr. Asilis said, is that owing to the low federal-funds rate and buying by the Bank of Japan and other central banks, the 10-year Treasury yield, at 3.75%, has become unnaturally low — meaning that it implies a far higher level for the S&P than really may be justified.

Mr. Yardeni of Prudential Equity concurs, saying that a more reasonable yield on the 10-year would be 5%. Still, on that basis, the S&P 500 would be valued fairly at 1280, about 15% higher than it is now.

“I think that stocks are undervalued and bonds are overvalued,” he said.

Mr. Asilis said that the Fed model is more useful as a valuation tool when earnings growth is on the rise. When the profits cycle peaks, and earnings growth begins to decelerate, it isn’t as reliable, he said.

For Cliff Asness, managing principal at the hedge fund AQR Capital Management and a longtime critic of the Fed model, the problems with the metric cut even deeper. Treasury yields are a forecast for future inflation — they rise and fall on inflation expectations — but when inflation falls, profits growth tends to slow as well, Mr. Asness said. Stocks’ price-to-earnings ratios shouldn’t vary according to the rate of inflation, because their earnings already do.

Stock returns should decline when inflation slows, Mr. Asness said. “People get fooled by Fed-model thinking into paying high [price/earnings ratios] for stocks.”

Mr. Asness said that the transcripts of Federal Open Market Committee’s February 1997 meeting suggest Fed Chairman Alan Greenspan may share his view. At the meeting, Mr. Greenspan equated interest rates with the rate of economic growth and then said that it appeared to him that the stock market was forecasting that corporate profits would grow significantly more quickly than the overall economy. For this to happen there would need to be a rise in profit margins, which Mr. Greenspan deemed improbable.

Despite these objections, Morgan Stanley senior investment strategist Byron Wien, who long has used a valuation tool that compares Treasury and earnings yields, said that such models still have validity. Treasury yields aren’t necessarily a forecast of earnings growth, he said. Otherwise it would be hard to square the strong earnings growth and low Treasury yields of the past year.

He said Treasury yields have fallen too low, and so he doesn’t believe that his model’s heady target is valid. But still, he thinks his model is saying something.

“I trust the directional message of the model, but not the magnitude,” he said.

Earnings estimates are too high.

Analysts lag reality. Too many assume earnings increase in a linear fashion.

KK-

Is CAPEX going to save us too????

Ciao

MS

I think it only became popular because it was a good sales aid for the sell side: sounded sort of “smart” or “scientific” without being too complicated for the retail investor to understand.

This model is really really dumb. It compares apples (bond yields which are nominal) to oranges (equity yields which are real).

The Modigliani-Cohn hypothesis from 1979 and from a nobel prizing winning economist lays it out very clearly. Here is a summary of what it says and more recent analysis: http://www.nber.org/digest/oct04/w10263.html .

At the end of the day, we should all keep our mouths shut because this “inflation illusion” creates incredible investment opportunties for those in the know.

Serious value investors (including Buffett) use 5 year or (preferably) 10 year trailing earnings, rather than “predicted” earnings. The ratios won’t be exactly the same, but it might be interesting to graph it.

Will we have to reach the point of dividend yields exceeding bond yields before people think they are a buy as used to be the case in the 50s? That would only mean a drop of say 50%?

Lord, I can think of quite a few large cap equities with “safe” dividend yields that are higher than the 10 year, currently @ 3.6%. Tobacco, pharma, chemicals, foods,are good places to look. Banks of course are suspect, but I wouldn’t overlook those either.

I think the profit margin numbers are misleading to some degree due to their influence by financials over the past 5 years. There is a good chart in Business Week that shows non-financial companies’ profits have been tracking close to historic norms. Of course all this indicates is that financials are still huge shorts.

Not disagreeing with the main points. Just want to add two comments: 1) The fed model is not officially a fed model; 2) There are ways to use only past earnings to time the market, not in the sense that it can always get the direction right, but in the sense that it usually does better than buy-and-hold:

http://www.kc.frb.org/PUBLICAT/RESWKPAP/PDF/RWP02-01.pdf

I agree the fed model is useless, but another model I follow is also very bullish, the specialist shorts, look at the invtools.com chart. any thoughts on why these xperts are signalling bull?

Alan Greenspan agrees with your post. Federal Reserve Board Publication 2000 – 05 written by Fed economist Michael Kiley concluded the Gordon Model (Fed Model) to value the stock market is flawed and unusable. Kiley’s article states on page 5,6 that he was told by Mr. Greenspan that when he spoke in 1996 of irrational exuberance he was specifically referring to the q ratio and SP price/dividend ratio to value the stock market, not the Fed model.

Barry, I have a more complex version of the “Fed Model” that is more rigorous:

http://alephblog.com/2007/07/09/the-fed-model/

There are still limitations to it, and I describe them at the end. People make too much out of the Fed model, and try to make arguments that the market is absolutely cheap, when all it does is measure relative cheapness to bonds.

I’m pretty sure I read the other day on Bloomberg that the p/e on the DJStoxx50 in Europe was close to 11. I can’t retrieve the article anywhere but I would love to know if anyone could verify that that 11 p/e is correct. If that is accurate I think it sheds light on how far the US market can fall from here just on multiple compression. I can’t see any reason at all that our market should sell at a 25% premium multiple to European blue chips in today’s bearish environment.

For accuracy, it is better to use after-tax corporate profit, adjusted for short and long-run rents, relative to tangible corporate assets x 100, not GDP.

On this basis, the avg. rate of corp. profit in the U.S. has been declining ever since the 1960s*. I would note as well that global firms’ avg rate of profit has since at least 1988 been quite low.

*Adjusted avg profit rate

(500 largest U.S. firms)

1954-1959 — 7.71

1960-1969 — 7.15

1970-1979 — 6.30

1980-1989 — 5.30

1990-1999 — 4.02 (2.29 without adjustment for rent)

2000-2002 — 3.30 (1.32 without ” ” ” )

Tellingly, there has been a long period now during which, on the above decade by decade scale, avg rate of profit resides below 10-yr Treasury yields.

Equities and other financial assets prices have been inflated well beyond what more standard analysis implies; the gap between price and profit has become very extreme. Under these circumstances and with the evident failing of price support policies, price falls to and below value.