Responding to Wallison’s Latest Defense of His Flawed Financial Crisis Inquiry Commission Dissent

By David Min

July 2011

>

originally published at American Progress.org

>

Introduction

If you’ve been closely following the housing finance reform debate, you may have come across a pair of shrill blog posts penned by Peter Wallison, a senior fellow at the American Enterprise Institute and a Republican appointee to the Financial Crisis Inquiry Commission. He responded to my February 2011 article, “Faulty Conclusions Based on Shoddy Foundations,” which criticized the research underlying Wallison’s dissent from the majority of the members of that commission, and his contention that U.S. affordable housing policies caused the global financial crisis.

In these blog posts on The American Spectator’s blog on May 24 and on AEI’s blog on May 26, Wallison criticizes ”Faulty Conclusions” as “fallacious,” “fraudulent,” and “deceptive”; claims that it contains a “fake” chart; and describes the article as a “political screed.”

As I describe below, these accusations are baseless and distract from the fact that Wallison does not actually address the main arguments of “Faulty Conclusions.” Wallison does not contradict the claim that his FCIC dissent depends critically on the categorization of millions of home mortgage loans as “high risk” that are not actually high risk. Wallison also fails to answer other serious issues with his arguments that were pointed out in “Faulty Conclusions.”

This issue brief will reexamine my core criticisms of Wallison’s dissent from the Financial Crisis Inquiry Commission and respond to his criticisms of my column “Faulty Conclusions.”

Background

Wallison, of course, wrote a lonely dissent from both the Financial Crisis Inquiry Commission majority report and from his fellow Republican commissioners, in which he alone blamed the global financial crisis on U.S. affordable housing policies. This argument is clearly contradicted by the facts, including the following:

• Parallel bubble-bust cycles occurred outside of the residential housing markets (for example, in commercial real estate and consumer credit).

• Parallel financial crises struck other countries, which did not have analogous affordable housing policies

• The U.S. government’s market share of home mortgages was actually declining precipitously during the housing bubble of the 2000s.

These facts are irrefutable.

Wallison’s argument, which places most of the blame on the affordable housing goals of the former government-sponsored enterprises Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac before they fell into government conservatorship in 2008, also ignores the actual delinquency rates. As David Abromowitz and I noted in December 2010:

“Mortgages originated for private securitization defaulted at much higher rates than those originated for Fannie and Freddie securitization, even when controlling for all other factors (such as the fact that Fannie and Freddie securitized virtually no subprime loans). Overall, private securitization mortgages defaulted at more than six times the rate of those originated for Fannie and Freddie securitization.”

So how did Wallison get to the conclusion that it was federal affordable housing policies that caused the crisis, despite the countervailing evidence? As Phil Angelides, chairman of the FCIC, has stated, “The source for this newfound wisdom [is] shopworn data, produced by a consultant to the corporate-funded American Enterprise Institute, which was analyzed and debunked by the FCIC Report.”

Angelides is of course referring to Wallison’s AEI colleague Edward Pinto. Wallison’s conclusion that federal affordable housing policies are primarily responsible for the financial crisis is based entirely on the research conclusions of Pinto, who finds that there are 27 million “subprime” or “high-risk” loans outstanding, with approximately 19.25 million of these attributable to the federal government’s affordable housing policies. As I point out in “Faulty Conclusions,” Pinto only gets to these numbers (which are radically divergent from all other estimates—for example, the nonpartisan Government Accountability Office estimates that there are only 4.59 million high-risk loans outstanding) by making a series of very problematic and unjustified assumptions.

Case in point: To support his claim that the Community Reinvestment Act, which requires regulated banks and thrifts to provide credit nondiscriminatorily to low- and moderate-income borrowers, caused the origination of 2.24 million outstanding “high-risk” mortgages, Pinto includes many loans originated by lenders who were not even subject to CRA. In fact, most of the “high-risk” loans Pinto attributes to CRA were not eligible for CRA credit.

Similarly, in arguing that Fannie and Freddie’s affordable housing goals caused the origination of 12 million “subprime” and equivalently “high-risk” loans, Pinto includes millions of loans that would not typically qualify for those goals. In fact, the vast majority (65 percent) of the “high-risk” loans Pinto attributes to the affordable housing goals of Fannie and Freddie fall into this category.

Wallison does not address these and other problems with Pinto’s research identified in “Faulty Conclusions.” Instead, he focuses all of his energies on defending one of my main critiques of Pinto’s work—that Pinto’s unilateral expansion of the definitions of “subprime,” “Alt-A,” and “high-risk” mortgages is both misleading and unjustified. So let’s deconstruct his attack on my research to demonstrate once again why he is simply wrong about the genesis of the U.S. housing crisis.

Wallison’s response

So how does Wallison go about defending Pinto’s work? He offers a series of disparate charges against the argument that Pinto’s expansion of the “high-risk” loan category is inappropriate. Notably, he does not actually address the central issue—that Pinto categorizes as “high risk” many millions of mortgages that are demonstrably not high risk. Let’s go over his main criticisms in turn.

Claim: It’s simply a disagreement over the correct meaning of “high-risk” lending

In his first blog post, published on May 24 on The American Spectator’s blog, Wallison summarizes “Faulty Conclusions” as merely a minor criticism about Pinto’s usages of the terms “subprime” and “Alt-A,” one that misunderstands the true intent of what Pinto is doing. Here is what Wallison says:

[Min is] arguing that Pinto’s definitions of subprime and Alt-A loans are not consistent with the definitions others have used for data collection and analysis. In other words, Pinto has used his own definitions to analyze the data in a new way.[i]

As the Financial Crisis Inquiry Commission and Pinto, among others, have all noted, the conventional definitions for “subprime” and “Alt-A” are imprecise, but generally refer to industry categorizations of loans with high-risk characteristics, loans made to high-risk borrowers, or loans with incomplete documentation of income or assets. Wallison is contending here that the central argument of “Faulty Conclusions” is simply a complaint that Pinto expanded the definitions of these terms, without considering the question of whether Pinto’s revised definitions actually make sense. This is, as anyone who’s actually read “Faulty Conclusions” would know, not accurate.

Pinto’s research does deserve criticism for its unilateral expansion of the terms “subprime,” “Alt-A,” and “high risk,” because it is confusing. For example, when Wallison, as he has done, cites a 25 percent serious delinquency rate for subprime mortgages (referring to the delinquency rate for actual subprime mortgages) and then states that there are 27 million outstanding subprime mortgages (referring to Pinto’s expanded definition of “subprime”), he is comparing apples and oranges in a very misleading way.

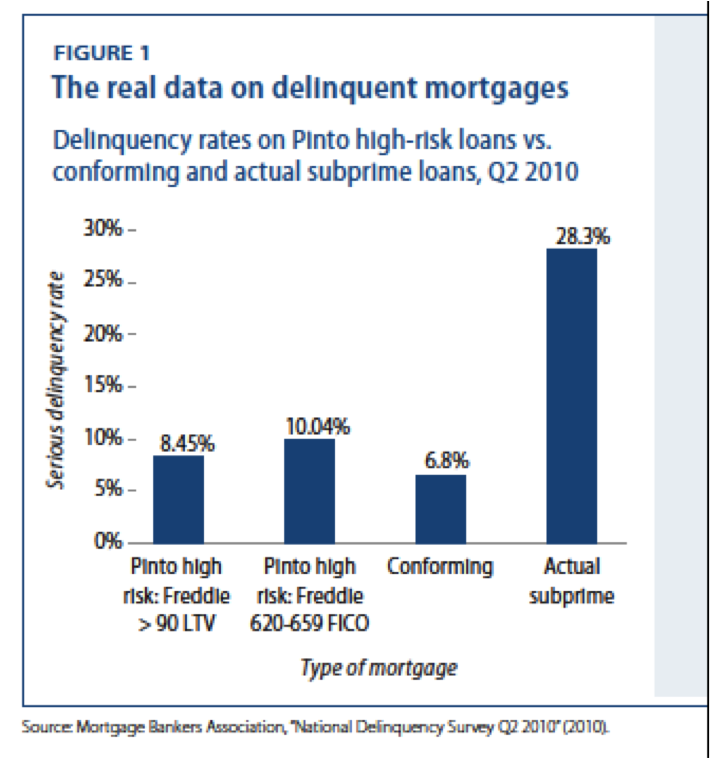

But contrary to Wallison’s assertion, this was not the entirety of “Faulty Conclusions’” criticism of Pinto’s newly invented definitions of “subprime” and “Alt-A.” Pinto’s expanded definitions are not only confusing but also unjustified. Pinto’s expansion of “high-risk” loans occurs primarily by including all loans made to borrowers with a FICO credit score of between 620 and 659 and all loans with a loan-to-value ratio of more than 90. Not only are these loans not generally understood to be “high risk,” but as demonstrated in the below chart from “Faulty Conclusions,” calling them “high risk” is inconsistent with their delinquency rates. These newly dubbed “high-risk” loans look much more like prime conforming loans than actual high-risk loans.

Claim: “Faulty Conclusions” includes a “fake” chart

Wallison also criticizes “Faulty Conclusions,” this time in a May 26 post on AEI’s blog, for relying on a “fake” chart, namely the one above. Specifically, Wallison states that this chart is “mislabeled as coming from the Mortgage Bankers Association’s (MBA) National Delinquency Survey for the second quarter of 2010,” and implies that this was an attempt to mislead readers into thinking that this chart was created by the MBA.

It is true that the chart is missing a line of attribution. Somewhere in the process of creating, editing, and posting that chart, a reference to Freddie Mac’s Second Quarter 2010 Financial Results Supplement got dropped from the chart itself. But the missing reference is actually contained in the accompanying text, immediately preceding the chart in question on pages 7–8, which both introduces the delinquency figures used in this chart and clearly sources them to the MBA’s National Delinquency Survey and Freddie Mac’s Second Quarter 2010 Financial Results Supplement.

In other words, Wallison’s accusation that this chart was “fake” and meant to “deceive” readers is baseless and contradicted by the actual text of “Faulty Conclusions.”

Claim: “Faulty Conclusions” overlooks Fannie and Freddie’s purchases of actual high-risk loans

Wallison also contends that the analysis in “Faulty Conclusions” overlooked Fannie and Freddie’s exposure to actual high-risk loans, through their purchases of AAA-rated subprime private-label mortgage-backed securities—those securities issued by investment banks and other private financial institutions, which are not tied to the federal government or its affordable housing policies. The implication is that Fannie and Freddie were creating most of the demand for these privately issued securities, which most analysts blame for the housing crisis. This claim actually gets to the core of the problem with Wallison’s argument.

It is of course well known, including by their regulator, the Federal Housing Finance Agency, that Fannie and Freddie were responsible for some actual high-risk loans, primarily through their purchases of high-risk private-label securities for their investment portfolio as well as through purchases of actual high-risk loans for their core securitization business. Yet as Wallison knows, this actual high-risk activity by Fannie and Freddie was neither sufficient in volume nor did it come at the right time to persuasively argue that the two mortgage finance giants drove the surge in actual high-risk lending we saw in the 2000s.

Did Fannie and Freddie buy high-risk mortgage-backed securities? Yes. But they did not buy enough of them to be blamed for the mortgage crisis.[ii] Highly respected analysts who have looked at these data in much greater detail than Wallison, Pinto, or myself, including the nonpartisan Government Accountability Office, the Harvard Joint Center for Housing Studies, the Financial Crisis Inquiry Commission majority, the Federal Housing Finance Agency, and virtually all academics, have all rejected the Wallison/Pinto argument that federal affordable housing policies were responsible for the proliferation of actual high-risk mortgages over the past decade.[iii]

Indeed, it is noteworthy that Wallison’s fellow Republicans on the Financial Crisis Inquiry Commission—Bill Thomas, Keith Hennessey, and Douglas Holtz-Eakin, all of whom are staunch conservatives—rejected Wallison’s argument as well.

This is why neither Wallison nor Pinto try to make the argument that the federal government was responsible for the proliferation of actual high-risk lending that occurred in the past decade, as such a claim would be quickly rejected as ridiculous. Instead, what Wallison and Pinto do—the key to their argument—is to expand the definition of “high risk” and “subprime” to include new categories of loans not ordinarily understood to be high risk. This expansion of “high-risk” lending is essential to the Wallison/Pinto argument that the mortgage crisis was caused by federal affordable housing policies.

Pointing to the fact that Fannie and Freddie bought some actual high-risk PLSs is thus irrelevant and does not address the claim that Pinto’s research relies critically on an improper and unjustified expansion of “high-risk” lending.

Claim: “Faulty Conclusions” fails to criticize all of Pinto’s “high-risk” categories of loans

Another Wallison criticism of “Faulty Conclusions” is that it mainly criticizes only two categories of Pinto’s “high-risk” loans. The first category is those with a FICO score between 620 and 659, or FICO 620-659 loans in mortgage industry parlance. The second category is high-risk loans with a loan-to-value ratio of more than 90 percent, or LTV>90 loans. In particular, Wallison takes exception to the fact that this criticism does not “mention the mortgages below 620 FICO … [of which] 14.4 percent were also seriously delinquent.”[iv]

There are two reasons I did not address these particular loans to borrowers with FICO scores under 620 in “Faulty Conclusions.” First, this is actually a relatively insignificant category of loans for Fannie and Freddie due to the heightened regulation for risk they enjoyed as specially chartered entities, which barred them from taking on excessive amounts of risk (although this regulation was clearly insufficient).

Loans made to borrowers with FICO scores under 620 account for only $60.8 billion of the $1.077 trillion in “high-risk” loans Pinto claims are held by Freddie Mac,[v] and a similarly small percentage of the “high-risk” loans Pinto claims are held by Fannie Mae.[vi] As a result, whether or not one criticizes Pinto’s description of these loans as “high risk” is immaterial. Adding them to FICO 620-659 loans held by Freddie Mac yields us a serious delinquency rate of 11.4 percent, compared to the 10.04 percent serious delinquency rate I listed for FICO 620-659 loans.[vii]

In other words, whether one criticizes or does not criticize Pinto’s characterization of loans made to borrowers with FICO scores under 620 as “high risk” is irrelevant. It does not change the basic point that these loans look categorically different from truly high-risk loans, which were originated almost entirely for private-label securitization and suffer a serious delinquency rate of more than 28 percent.

The second reason I did not criticize Pinto’s categorization of home mortgages with FICO scores below 620 as “high risk” is because, unlike with LTV>90 and FICO 620-659 loans, there is actually some legitimate debate over whether this particular characteristic should be considered high risk.[viii]

Contrary to Wallison’s assertion, Pinto’s unique contribution to the debate over the causes of the financial crisis was not the discovery that Fannie and Freddie had taken on some legitimately high-risk loans. As I note above, this fact is well known, including by Fannie and Freddie’s regulator. Rather, Pinto’s unique contribution to the debate was the creation of a new “high risk” category of loans, one which combines actual high-risk loans, which most everyone agrees are high risk, with new categories of loans that very few people think of as high risk.

To adapt the analogy Wallison uses in calling subprime mortgages bananas and Alt-A mortgages peaches, what Wallison is doing is offering up a medley of vegetables and fruits, prepared by Chef Pinto, and calling it a fruit salad. And to try to prove it is a fruit salad, Wallison will typically point out that it has characteristics of fruit, such as delinquency rates, which are higher than other types of loans.[ix]

What I tried to show in “Faulty Conclusions,” which is represented in the chart above, is that this fruit salad includes lots of vegetables, including corn (LTV>90) and asparagus (FICO 620-659), which do not have the characteristics of fruit. Moreover, the inclusion of these vegetables is integral to Pinto’s conclusion that affordable housing policies caused the crisis.

Rather than defend Pinto’s inclusion of loans that are not high risk in a “high-risk” category, Wallison chooses to criticize my omission of tomatoes (FICO<620) from my analysis. Of course, there are some legitimate reasons to claim that a tomato is a fruit, just as there are legitimate reasons to claim that mortgages with FICO<620 loans are high risk. But this still begs the question of whether there is any legitimate basis to label corn (LTV>90) and asparagus (FICO 620-659) as fruits.

More questionable numbers from Pinto

While Wallison avoided responding to the significant evidence offered in “Faulty Conclusions” showing that Pinto’s “high risk” loan categories of LTV>90 and FICO 620-659 loans are not actually high risk, Gene Epstein, the economics editor at Barron’s, does try to take on this claim with a little bit of help from Pinto. Specifically, Epstein criticizes “Faulty Conclusions’” comparison of the delinquency rates for LTV>90 and FICO 620-659 loans with the Mortgage Bankers Association’s National Delinquency Survey’s 6.8 percent delinquency rate for prime conforming loans. Relying on calculations performed by Pinto, Epstein argues that the MBA’s category of prime conforming loans actually contains many “high-risk” products:

Those “conforming” mortgages with the 6.8 percent rate include, for example, a lot of loans with below-660 FICO scores. When I asked Pinto to back all his high-risk categories out of the MBA data on “prime” loans, he found a 3.4 percent delinquency rate, or half as great as 6.8 percent.

Essentially, Epstein claims that prime conforming loans are not actually the safest possible category of mortgages, and so using them as a benchmark leads to misleading conclusions.

This sounds convincing but it’s wrong for two reasons. First, it is impossible to “back out” Pinto’s high-risk categories from the MBA’s delinquency numbers because the MBA doesn’t actually record its delinquency data based on the criteria used by Pinto. As MBA Vice President of Research and Economics Mike Fratantoni emailed to me:

“In our National Delinquency Survey, we receive aggregated data from servicers, not loan level data. Servicers identify their book or portions of their book as prime or subprime, we do not specify a specific FICO score cutoff. For that reason, there is no means for us to “back out” high-risk categories from prime loans.”

Moreover, as Fratantoni explained, under the MBA’s methodology, prime adjustable-rate mortgages, which were suffering a 13.75 percent delinquency rate, included some high-risk products (most notably option ARMs), but prime fixed-rate mortgages, which were suffering a 5.98 percent delinquency rate, did not include any of Pinto’s “high-risk” loans. Said Fratantoni:

“The prime FRM category does not include any [Pinto] high-risk products, but it also experienced a significant increase in delinquency and foreclosure rates due to the spike in unemployment and the steep drop in home prices.”

In short, not only is Pinto claiming that he can “back out” his numbers from the MBA’s delinquency survey—something the MBA says it cannot do itself—but Pinto’s “backed out” delinquency rate of 3.4 percent for fixed-rate and adjustable-rate prime mortgages is far lower than the MBA’s delinquency rate of 5.98 percent for fixed-rate prime mortgages, which contain neither Pinto’s “high-risk” mortgages nor adjustable-rate mortgages (which have defaulted at much higher rates than fixed-rate mortgages).

Clearly, Pinto is relying on some very large and unstated assumptions here to “back out” the MBA’s numbers.

The second reason Epstein is wrong about Pinto’s numbers is that he’s missing the key point being made in this comparison, which was that the unique categories of “high-risk” loans used by Wallison and Pinto contain large numbers of mortgages that are not actually high risk (and which could not be legitimately understood to have caused the mortgage crisis), as reflected by their relative delinquency rates.

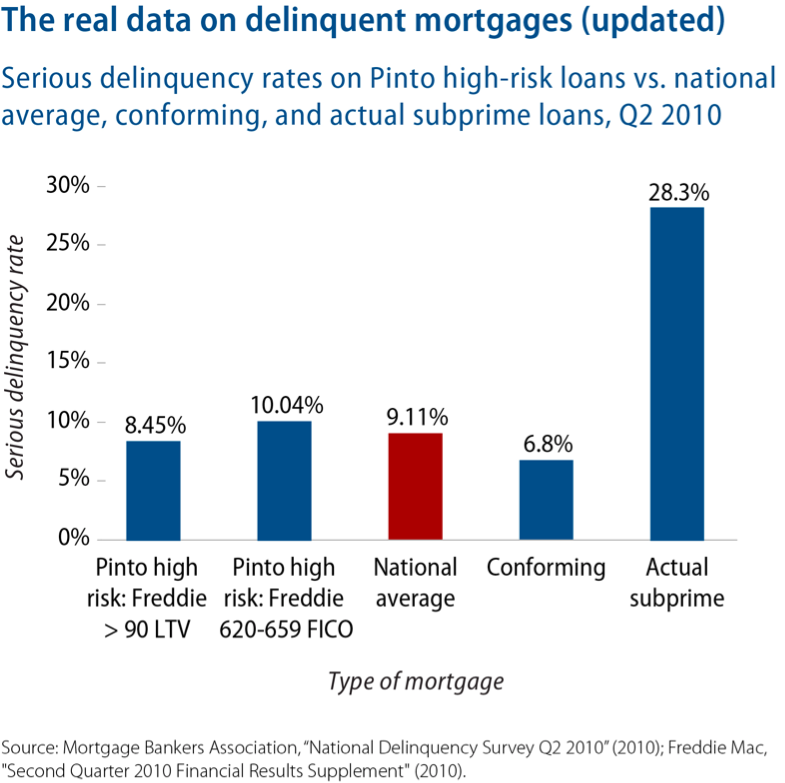

The point of this comparison was not, as Epstein seems to assume, to imply that LTV>90 and FICO 620-659 mortgages are the safest loans possible, but simply to point out that it defies all logic to call these loan categories “high risk.” As such, it does not matter whether Pinto can or cannot back out a safer version of “prime conforming” than the MBA. Rather, the important question is whether and to what extent these loan categories can justifiably be called “high risk.” Looking at this from a different perspective, Pinto’s newly invented “high-risk” loans have serious delinquency rates that are essentially identical to the national average of 9.11 percent (again from the MBA’s National Delinquency Survey for Q2 2010). (see chart below)

It is difficult to understand how these loans are “high risk” unless one claims that all U.S. mortgages are “high risk,” in which case one would expect to see a much higher national delinquency rate, particularly given the historically high housing market price declines and unemployment levels we have experienced.[x]

Chefs Wallison and Pinto overlooked a couple of ripe fruits

Clearly, the Wallison/Pinto argument depends critically on an enormous expansion of the definition of “high-risk” lending. As such, it is very curious that they do not include two types of loans that are significantly riskier than LTV>90 and FICO 620-659 mortgages, based on the delinquency data, specifically:

- Loans that were originated for private-label securitization

- Loans with adjustable rates[xi]

Loans originated for these two categories have higher delinquency rates than LTV>90 and FICO 620-659 loans, and yet Wallison and Pinto ignore them.

Why? One answer may be that these loans were overwhelmingly originated for private-label securitization,[xii] a fact which directly contradicts Wallison’s preferred argument that the government was to blame for high-risk mortgages.

Whether or not the omission of these types of loans from their expanded definition of “high-risk” mortgages was ideological or not, it seems fairly inexcusable. Countless analysts, including the staff of the Federal Crisis Inquiry Commission where Wallison was a commissioner, have noted that mortgages originated for private-label securitization and mortgages with adjustable rates performed very poorly.

Conclusion

It is unfortunate that Wallison, who is a prominent conservative voice on financial markets issues, consistently fails to appreciate the deep problems with the Pinto research he has adopted as his own. As I pointed out in “Faulty Conclusions,” Pinto’s research is critically dependent on the broad and unjustified expansion of the definitions of “subprime,” “Alt-A,” and “high-risk” loans.

Moreover, and perhaps reflecting his ideological bias, Pinto fails to include two loan characteristics that are actually more indicative of risk than his newly added “high-risk” loans—whether a loan has an adjustable rate and whether a loan is originated for private-label securitization. These loans are, of course, overwhelmingly attributable to the private sector. And without question they are the genesis of the U.S. housing and financial crises.

David Min is the Associate Director for Financial Markets Policy at the Center for American Progress. He leads the activities of the Mortgage Finance Working Group, a group of leading experts, academics, and progressive stakeholders in housing finance first assembled by the Center for American Progress in 2008 to better understand the causes of the mortgage crisis and create a framework for the future of the U.S. mortgage system.

Endnotes

[i] Peter Wallison, “The True Story of the Financial Crisis—Responding to Criticism,” The American Spectator Blog, May 24, 2011, available at http://spectator.org/blog/2011/05/24/the-true-story-of-the-financia.

[ii] Jason Thomas and Robert Van Order of George Washington University explicitly reject the claim that the affordable housing goals were a major driver of demand for subprime MBSs, for at least three reasons. First, Fannie and Freddie were only buying AAA-rated securities, which means that others were buying the riskier, lower-rated subprime securities. Second, unlike the lower-rated tranches, AAA-rated tranches had very short durations, which means that to a large degree, the two mortgage finance giants’ purchases of subprime securities were simply replacing their own expiring holdings. Third, Fannie and Freddie only purchased mortgage-backed securities, not derivatives such as collateralized debt obligations or credit default swaps. Thus, looking at their purchases of subprime mortgage-backed securities actually significantly overstates their share of the total offering of subprime securities (since synthetic collateralized debt obligations and credit default swaps could mimic the risk/reward offerings of mortgage-backed securities). Moreover, as Thomas and Van Order point out, the fact that synthetic CDOs and CDSs could be created without originating new loans essentially meant that the supply of subprime securities was infinite.

[iii] This blame primarily goes to private-label securitization, which, as I noted in “Faulty Conclusions,” is responsible for only 13 percent of all outstanding loans but 42 percent of all seriously delinquent loans. Conversely, Fannie and Freddie are responsible for 57 percent of all outstanding loans but only 22 percent of all seriously delinquent loans. If, as Wallison and Pinto claim, Fannie and Freddie were responsible for 12 million high-risk loans (of 27 million total high-risk loans), then one would expect to see an exponentially higher delinquency rate for Fannie and Freddie, and a much larger share of delinquent loans.

[iv] One other fundamental problem with the Wallison/Pinto argument that I did not raise in “Faulty Conclusions” is tied to this point. In general, the riskiness of a particular loan is not integrally tied to a single characteristic but rather to multiple characteristics, or “risk layering.” Loans with low down payments may or may not be high risk, depending on their other attributes. Loans with low down payments, made to borrowers with bad credit histories and who have adjustable teaser rates, are truly high risk, which is why they are categorized as high risk by lenders. The underlying assumption of Pinto’s work is that judging the riskiness of loans based solely on single loan characteristics is more accurate than lender determinations of risk. This assumption not only ignores one of the key principles of loan underwriting; it is, as I point out in “Faulty Conclusions,” contradicted by the delinquency data.

[v] Edward J. Pinto, “Sizing Total Federal Government and Federal Agency Contributions to Subprime and Alt-A Loans in U.S. First Mortgage Market as of 6.30.08,” Exhibit 2, p. 8–10, available at http://www.aei.org/docLib/Pinto-Sizing-Total-Federal-Contributions.pdf; “Freddie Mac’s Second Quarter 2008 Financial Results,” p. 26, available at http://www.freddiemac.com/investors/er/pdf/slides_080608.pdf. Using Freddie Mac’s Q2 2008 financial results, Pinto combines Freddie’s Alt-A loans with all of the different categories that comprise his newly invented “Alt-A by characteristic” and “subprime by characteristic,” and then multiplies these by 80 percent to account for overlaps between the different categories. Freddie Mac lists $76 billion in loans made to borrowers with FICO scores under 620. Applying the same 80 percent discount factor to this $76 billion leaves us with $60.8 billion, which is 5.6 percent of the $1.077 trillion in total “high-risk” loans Pinto calculates are held by Freddie Mac.

[vi] $101.92 billion.

[vii] “Freddie Mac’s Second Quarter 2008 Financial Results,” p. 26. Freddie Mac lists a 14.44 percent delinquency rate on $64.9 billion ($9.37 billion) in mortgage with FICO scores below 620, and a 10.04 percent delinquency rate on $141.5 billion ($14.21 billion) in mortgage with FICO scores of between 620 and 659. Merged together, Freddie has a 11.44 percent delinquency rate on these loans ($23.58 billion seriously delinquent out of $206.4 billion total).

[viii] For the same reasons, I did not criticize Pinto’s categorization of option ARMs, actual subprime (what Pinto calls “self-denominated” subprime), or actual Alt-A (what Pinto calls “self-denominated” Alt-A) loans as “high risk.”

[ix] This is done through a chart provided by Wallison, available at: Joseph Lawler, “The True Story of the Financial Crisis — Responding to Criticism,” The American Spectator Blog, May 24, 2011, available at http://spectator.org/blog/2011/05/24/the-true-story-of-the-financia; Peter J. Wallison, “Financial Crisis Inquiry Commission, Dissenting Statement” (Washington: American Enterprise Institute, 2011), p. 462, available at http://fcic-static.law.stanford.edu/cdn_media/fcic-reports/fcic_final_report_wallison_dissent.pdf. The chart describes a delinquency rate for Fannie and Freddie “high-risk” loans of 17.3 percent and 13.8 percent, respectively. There are serious problems with this chart as well. First, Wallison and Pinto use a 30-day delinquency rate rather than the nine-day serious delinquency rate typically used by serious most objective analysts. This, of course, has the effect of significantly increasing the stated delinquency rates. For example, Fannie Mae had a serious delinquency rate on these types of loans of only 9.36 percent, as compared to the 17.3 percent listed. Moreover, the decision to use 30-day delinquency rates rather than serious delinquency rates is a very curious one, because all of Wallison and Pinto’s listed data sources (Lender Processing Services, Fannie Mae, Freddie Mac) provide serious delinquency rate data, but only LPS offers 30-day delinquency rate data. As a result, Wallison and Pinto had to “convert” Fannie and Freddie’s serious delinquency rate into “estimated” 30- day delinquency rates. Nor do Wallison and Pinto provide a description of the methodology used or assumptions applied in making this conversion. No such conversion would have been necessary if they had used the standard 90-day delinquency rates. Wallison and Pinto could simply have provided the serious delinquency rates, but this may not have provided the numbers they preferred to see.

[x] By way of comparison, the delinquency rate for urban home mortgages in 1934 was about 50 percent. See: David C. Wheelock, “The Federal Response to Home Mortgage Distress: Lessons from the Great Depression,” Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis Review 90 (3) (2008): 138–139, available at http://research.stlouisfed.org/publications/review/08/05/Wheelock.pdf. As Wheelock notes, “comprehensive data on mortgage delinquency rates do not exist for the 1930s.” The delinquency rate for urban homes was compiled through a study of 22 cities by the Department of Commerce.

[xi] See, for example: Federal Housing Finance Agency, “Data on the Risk Characteristics and Performance of Single-Family Mortgages Originated from 2001 through 2008 and Financed in the Secondary Market” (2010), available at http://www.fhfa.gov/webfiles/16711/RiskChars9132010.pdf.

[xii] Of course, all loans originated for private-label securitization were originated for private-label securitization. Adjustable-rate loans were disproportionately attributable to PLS as well. Ibid, p. 3. (“Enterprise-acquired mortgages were predominantly fixed-rate loans. Such loans comprised 88 percent of all Enterprise-acquired mortgages originated between 2001 and 2008. … mortgages financed with private-label MBS were predominantly adjustable-rate loans. Such loans comprised 70 percent of mortgages financed with private-label MBS originated between 2001 and 2008.”)

What's been said:

Discussions found on the web: