Click to enlarge:

Reuters.com – Spain suffers as sentiment sours post-Greek election

Spanish bond yields hit a new euro-era high above seven percent and Italian yields jumped on Monday as initial relief after a pro-bailout victory in Greek elections gave way to pessimism about the huge problems still facing the currency bloc. The swift reversal in sentiment saw German Bund futures rise, quickly erasing early losses of over a full point, while European equities and the euro wiped out initial gains.Political parties in favor of Greece’s bailout lifeline began to try and forge a government on Monday after a narrow victory over radical leftists who wanted to tear up the existing aid agreement.That removed the risk of an imminent Greek exit from the currency bloc, but the slim margin left major doubts over how effectively a pro-bailout coalition could govern, with markets taking the view that Greece may still end up leaving the euro zone.”The Greek situation is still very, very precarious. They only just got the majority, but there are still a lot of headwinds there in terms of getting a coalition and then you’ve got Spain blowing up again – we’re not in great shape,” a trader said.Investors turned their attention back to Spain, the euro zone’s fourth-largest economy, where spiraling borrowing costs are threatening Madrid’s ability to fund itself and raising speculation that Spain may need a full-blown bailout.

Bloomberg.com – Spanish Yields at 7% Show Investors Slamming Door: Euro Credit

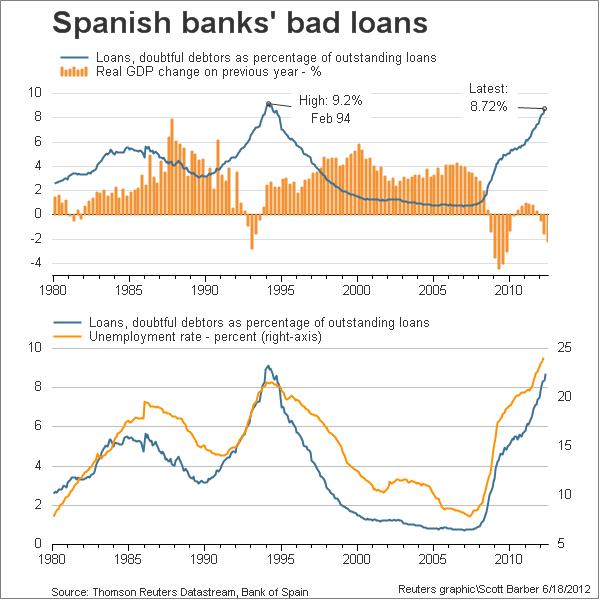

Investors who oversee more than $3.2 trillion expect Spain to become the fourth euro member to need external funding as borrowing costs surge to levels too punitive for the nation to finance its needs on the capital markets. Spanish debt has slumped, pushing the 10-year yield today to a euro-era record of 7.14 percent, as investors at Fidelity Investments, Frankfurt Trust and Principal Investment Management say the nation may lose market access. The bonds are the worst performers among 26 developed markets since June 9, when Economy Minister Luis de Guindos said he would request as much as 100 billion euros ($127 billion) of emergency loans from the euro area to shore up a Spanish banking system hobbled by bad assets. “Yields are at levels at which Spain can’t really afford to finance itself for more than a few months,” said Craig Veysey, head of fixed income at Principal Investment Management in London, part of Sanlam Group, which manages $72 billion. “The banking bailout doesn’t really help Spain’s credibility in the market and the probability is rising that it will be asking for a bailout for the sovereign.” Veysey said he doesn’t own Spanish government bonds and has no plans to purchase them. Prime Minister Mariano Rajoy called on Europe’s policy makers last week to do more to support Spanish bonds after the bank rescue failed to halt yields from climbing to levels at which Greece, Portugal and Ireland needed to seek help. His government is battling to reduce the nation’s debt load as the recession in the euro area’s fourth-largest economy deepens, leaving the jobless rate at more than 24 percent.

The Economist – Going to extra time

The €100 billion pledged to help Spain was meant to rescue the banks and calm the euro zone. Instead it has added to the drama

IT WAS a victory for the euro. It was a credit line. It was “the thing that happened yesterday”. The one way Spanish prime minister Mariano Rajoy refused to describe the pledge of €100 billion ($125 billion) from other euro-zone countries to recapitalise Spain’s banks was as a “bail-out”. Nor was it a rescue, the economy minister, Luis de Guindos, insisted; just “a loan with very favourable conditions”. Regardless of the conditions, the outcome was less than favourable. The package had been put together during a series of rushed videoconferences of euro-zone finance ministers on June 9th. The European Commission president, José Manuel Barroso, says he pushed Mr Rajoy, who had previously denied the need for any deal, into accepting one. Mr Rajoy has claimed it was he who did the forcing, insisting on a deal focused only on the banks. What is certain is that a need to calm markets before the Greek election on June 17th piled on the pressure. The markets were not calmed. By June 12th bond yields were higher than they have been since the country adopted the euro in 1999; if they stay that high for long the kingdom of Spain itself would need a bail-out (see chart 1). Even without government circumlocution, enough was fuzzy about the deal to have investors worried. Yet some things were clear: while Spain now has a plausible plan to recapitalise its banks, the new money does little to resolve the Spanish economy’s other fundamental problems.

Source: Bianco Research